Last year, before IoT monitoring became a thing, experts were worrying about zombie computers. While they worried about powerful desktop PCs, a fifth column of helpful little home devices has crept under the radar and connected to the world wide web. Like sleeper cells waiting for the order to attack they lived among us; recording our favorite shows, regulating the temperature or light in our homes, watering our plants. Then, on October 21st, they were hijacked to send millions of requests to a bunch of service providers’ servers, laying low Internet giants such as Twitter or PayPal, and disrupting Internet services across the USA.

Today is Cyber Monday, and new regiments of these bots are marching off the shelves, and, although logically, consumer confidence in these devices is down, demand has hardly been affected, with Black Friday and Cyber Monday about to kick off our annual orgy of consumerism lasting through to the hangover of the New Year. How can we ensure that these bots are safe? During the present rush to market of devices, designed with functionality rather than security in mind, the focus is all on what they can do for us and very little on what might be done to us through them.

This last attack are came through household consumer goods, but what about pacemakers, automated saline or insulin drips in hospitals, or driverless cars? These devices also belong to the Internet of Things, a catchall term to describe any device with in Internet connection, however diverse the function of the device may be; programing a DVR doesn’t seem to have much in common with integrating cardiac monitoring into a hospital’s IT infrastructure, or hunting Pokemons in the park, with sending a delivery truck on a preprogrammed delivery run down rural backroads.

Certainly the introduction of legislation could be a start, if we had years to address the problem, which we don’t. It seems like the solution is going to have to come from inside the industry, as is so often the case (for good and bad), and it is clear that IoT monitoring is going to have a part to play. Certainly, the industry could take some responsibility for introducing default protocols in case of anomalous behavior in their devices, but in their defect, IoT monitoring will inevitably step up to the plate. DDoS attacks aside, where else can monitoring play a role in helping to administrate this proliferation of interconnected devices?

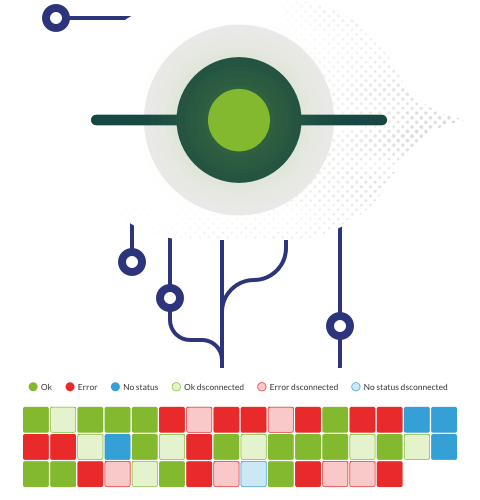

Monitoring household devices, and making damage control provisions for similar DDoS attacks would seem to be a given, and hardly a technological challenge; the tool should be able to tell you where the attack originates, and which components and elements of your network are affected. This in turn lets you know how your business or organization could be impacted and allow you take action.

In other areas we will see more positive, pro-active benefits of IoT monitoring. Hospitals don’t like to acknowledge it, but mistakes happen; late nights, long shifts, high patient turnover, even illegible writing can play a part in a medical mix-up. Automating routine hospital tasks such as administrating medicines via drip, or regulating insulin delivery, is becoming the future standard, and monitoring those tasks, making them less prone to human error is highly achievable. You establish your parameters (the amount of medicine to be delivered, the frequency, etc.) and your automated system carries out its function faultlessly. The monitoring runs in the background, ensuring the system is working correctly.

What about when the subject is up and about? Now we have wearables (smart watch, heart rate monitors) and implantables (pacemakers), which can connect to the Internet, share data, collate it, analyze it, and generally provide a lot of health-related numbers to crunch Doctors and patients will soon be looking at these figures, represented graphically through an IoT monitoring platform.

We’re dealing with a problem of nomenclature as well as a security problem. Security is a question of corporate responsibility in terms of diversifying their default passwords, and anticipating how their bots will be integrated into a larger network. Once they’re in that larger system, monitoring can also play its own part. DDoS attacks are almost impossible to predict, due to the suddenness with which they happen, although it may be possible to identify anomalous network usage in terms of traffic spikes or bad requests. If our tool collates enough data, it could be used identify the circumstances leading up to an attack and give us a little wiggle room before the spam hits the fan.

Pandora FMS’s editorial team is made up of a group of writers and IT professionals with one thing in common: their passion for computer system monitoring. Pandora FMS’s editorial team is made up of a group of writers and IT professionals with one thing in common: their passion for computer system monitoring.