Open Hardware: The Past and Present

In the 1980s, Open Hardware made our society shake with the irruption of a giant: IBM® It seems that now in 2018 history will repeat itself!

Recently, we wrote on the blog a short story about supercomputers, as well as the big threat, without enough media coverage, about Spectre and Meltdown’s vulnerabilities. We will elaborate both articles in this post. We’ ll tell you about Open Architecture, Free Hardware and Open Hardware and their subtle differences.

Brief Historical Background

We always say that, if we don’t know where we come from, we’ll never know where we’re going. Although we have been using computers in a very useful way since the Second World War, a period that most of us have not experienced, we have known about computers in a domestic and massive way since the 1980s, and that is what many of us have experienced.

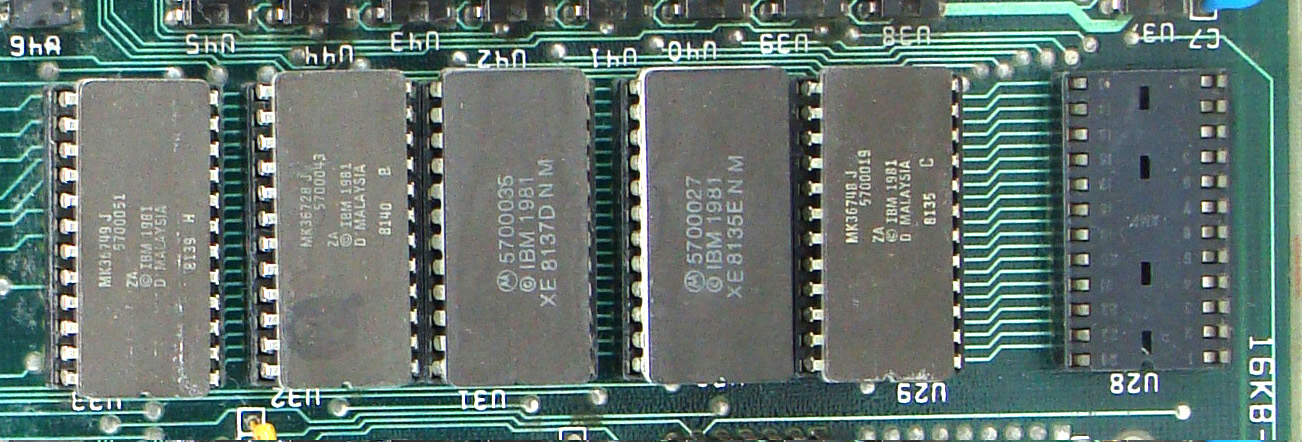

By the end of the 1970’s there were countless brands on the market, and yes, the Apple® company had also been born, which was starting to stand out from the rest, and this did not go unnoticed by the great Blue Giant® called Industrial Business Machines®, better known as IBM®. Does the phrase IBM® compatible ring a bell? IBM® has never lost its position in this server market thanks to its vertical integration: from the factory of its components and peripherals, operating systems, applications, user training and business support, all this is done by IBM® (and it continues to do so). So when they realised the potential for sales to small and medium-sized businesses, as well as to households, they realised that they were’late to the party’. They decided then, to save time, to choose the Open Architecture, and settled their operations in Boca Raton, in the state of Florida. This is where the Standard Industrial Architecture (SIA) was born, the precursor of the Open Hardware that we are discussing here today.

Former IBM building in Boca Raton, Florida (photo taken by Phillip Pessar in 2017 and published on Flickr)

After this announcement, many manufacturers began to build peripherals and accessories, as the technical specifications were very clear and widely known. What was the hidden card in the IBM® sleeve? Well, almost nothing, they reserved the opening of the motherboard BIOS by means of copyright, an essential component for this Open Architecture, and they charged for intellectual property rights to any manufacturer, under penalty of powerful lawsuits to those who dared to compete in this critical area (the code was within everyone’s reach, since IBM® published it in one of its manuals inadvertently).

Shortly thereafter Compaq® (acquired by Hewlett Packard® in 2002, assimilated as a division and now extinct) performed reverse engineering on the BIOS and won the legal case proving that it did not use any IBM® patents. Compaq® did not succeed in all its battles: IBM® commissioned a real army of lawyers to protect its 9,000 patents and, from all its searching and searching, realized that Compaq® violated one of them: they had to pay IBM® US$ 130 million for the right to use the copyright on just one of them.

Another IBM® mistake was to allow Microsoft® to sell the MS-DOS® operating system (which they had purchased from another programmer for US$80,000 and sold non-exclusively to IBM® as PC-DOS®) to those clone system manufacturers. In addition, by the year 2000, the term Wintel was well established in the computing community: Intel® refused to sign exclusive contracts for its 386 processors with IBM® in order to increase its sales in the clone market. However, IBM® did not give up and continued its fight, until in 2005, when it finally decided to sell the computer division to the Asian giant Lenovo®, which is the brand we buy today and many of us use because of the durability of its devices.

Lenovo Headquarters 2015 in Xibeiwang (photo wikipedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lenovo_western_headquarters_(20170707113944).jpg)

It was also a failed attempt in 1987 to reverse the use of Open Hardware with more restrictions in the famous and now extinct Micro Channel Architecture (MCA), which was not compatible with the software, which involved new compilations of all existing software running on IBM® compatible. But it wasn’t all hopeless for IBM®, nor for us as users: this model’s IBM PS/2® motherboards still come with VGA standard connectors and PS/2 mouse and keyboard connectors (although they are now disappearing in favor of USB and DVI/HDMI).

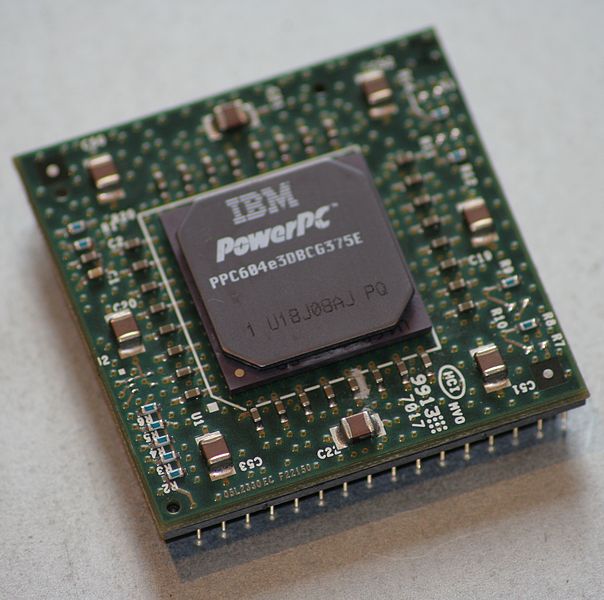

This story ends with Compaq’s quick response, and together with Zenith Data Systems®, Tandy®, HP®, Olivetti®, NEC®, AST Research®, Epson® and WYSE® created the Extended Industrial Standard Architecture (EISA) that evolved with the extinct VESA (ISA backward compatibility) and the one we currently use to write these lines: the Peripheral Component Interconnect bus (PCI and now evolved as PCI Express). The PCI bus was so new and powerful that even Apple® adopted it in 1995 for its Power Macintosh and, guess what, inside the Power Macintosh there was a processor called PowerPC from…. IBM®!

Open Hardware and Free Hardware

As you can see, the fact that we have the source code of an application or electronic device (and that it is available to millions of people and is well known) and that we can improve it does not mean that it is free of charge for our pockets, and the Open Hardware is an example of this. Free Hardware, on the other hand, does not place any restrictions (such as Free Software):

- With Open Hardware and Free Hardware, we can both use them how and where we want or need them.

- With Open Hardware and Free Hardware, both, we know how it works, and this is where the differences begin: any improvement we make to Open Hardware must be paid back to the company that owns the copyright, in order to know how much we must pay for the improvement we make ourselves. In this scenario, several alternatives may occur: we may be released from payment (but not the other clients) or, in the best of cases, paid by royalties, in other words, our authorship may be acknowledged (based on the knowledge that previously allowed us to know, in complete contrast to the case of the company Compaq® that we have mentioned).

- With Open Hardware and Free Hardware we can distribute the source code to third parties to facilitate its dissemination, as it is public, open and notorious code. However, making a profit from the Open Hardware will be impossible because we do not own the copyright, perhaps we could recover the value of the substrate (paper, DVD, etc.) where the information is contained.

- In the Free Hardware we will be able to share and even sell our improvements to third parties without any problems, but in the case of the Open Hardware we already saw in the zero point that is not allowed in any way or form.

Quote: “Directly said: with Open Hardware we will always have to pay the patent fees and any improvements we make will always belong to the company that owns the copyright“.

The Open Hardware and the lesson learned

IBM® learned from their mistakes, and the PowerPC processor was made in partnership with Motorola®, and Apple® was involved, with millions of customers eager to invest their savings in cutting-edge technology. Everything took an unexpected turn in 2007, when Steve Jobs announced that Apple® would start using Intel® processors and that they had always been prepared for them because they secretly also compiled their proprietary operating system on both hardware platforms.

Everything looked hopeless to the POWER processor… or so.

The point is that IBM® never cut back on developing and maintaining this processor, and never forgot that Intel® refused to sign any exclusive agreement, which was an unforgettable lesson for them (IBM®). So good and powerful are the POWER1 to POWER7 series processors that they were used in two of the thirteen most powerful supercomputers in Spain: the Magerit and the Marenostrum (I and II).

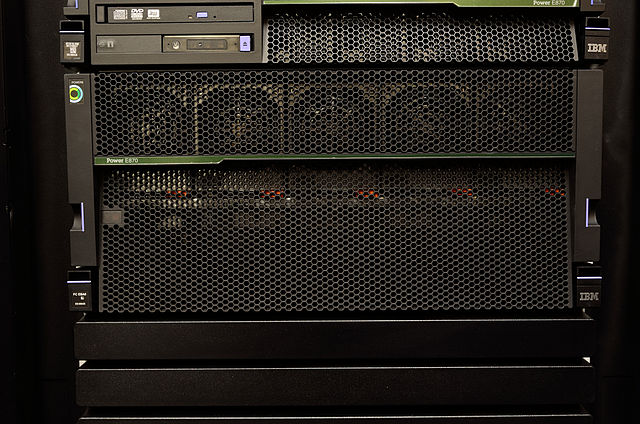

If you’ve come this far, you probably have the feeling that we’re earning a commission for advertising and “selling you this POWER9 processor” : each of these processors costs more than 5,000 euros to change (not to mention other components) and are intended – or intend – to dethrone the reign of the Intel® Xeon® on the large application and database servers. In fact, until 2013 they were only used on IBM® large servers, but in that year they sponsored the Open POWER Foundation.

The Open POWER Foundation

It is led by IBM® and the following Platinum Members: Google®, nVidia®, Micron®, Red Hat® and Ubuntu®. Its purpose is to “popularize” the use of these processors and eventually displace Intel® from its Web 2.0 site of honor. Copying the whole market is not an easy task, that’s why they must leave their niche in Unix® to reach Linux, which is present in 498 of the 500 most powerful supercomputers of today, and we know that if they use Linux they can be monitored with Pandora FMS in a reliable and precise way.

From this group that makes up the Open POWER Foundation, you may find it strange to see nVidia®, a video card manufacturer, how does this company fit into this supercomputer business and what does it have to do with Open Hardware?

POWER9 Features

To understand why nVidia® is interested in participating in the Open Hardware without really manufacturing anything with this paradigm, we will need to look very briefly at the capabilities and architecture of this POWER9 processor:

- They start from 24 cores and what is really interesting is their ability to connect to the new NVLink 2.0 standard, which allows parallel computing to nVidia® cards. This allows a high data throughput (25 Gbps) to be passed quickly to these auxiliary processors and every millisecond saved in data transmission and reception is a lot of computing power used by POWER9.

- They also support the PCI-Express 4.0 standard that allows up to 16 Gbps to connect any peripheral that needs to transmit data to the processor.

- The most important thing: boot security, as it is totally immune to attacks that corrupt the boot sector (in theory, a reboot will be enough to load the OS cleanly).

But wait, there’s more…

Unfortunately, on May 22, 2018, IBM® officially announced that although they were not exempt from the two Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities exposed in January 2018, a fourth of high severity was found at the beginning of May, which forced the publication of a correction by their official repositories and also the respective patches were given to Red Hat, SUSE and Canonical (Ubuntu) while the situation in future developments is being completely corrected (we speculate on the presentation of POWER10, by mere logic).

What does Open Hardware have to do with vulnerabilities in general? A lot was said about the very little time of grace offered by the researchers who discovered Spectre and Meltdown, which put at risk the security of countless equipment we use on websites such as banking platforms, the oil industry and nuclear power plants. IBM®, by delivering everything about the performance of its processors, opens up the possibility of early detection of design flaws involving vulnerability. Although this is a long-term task, it will pay off in the future.

Conclusions

The flexibilization of licenses and patents to spread knowledge about hardware will greatly help future companies to achieve the same results in different ways and forms, as Compaq® did last century and as history shows.

Programmer since 1993 at KS7000.net.ve (since 2014 free software solutions for commercial pharmacies in Venezuela). He writes regularly for Pandora FMS and offers advice on the forum . He is also an enthusiastic contributor to Wikipedia and Wikidata. He crushes iron in gyms and when he can, he also exercises cycling. Science fiction fan. Programmer since 1993 in KS7000.net.ve (since 2014 free software solutions for commercial pharmacies in Venezuela). He writes regularly for Pandora FMS and offers advice in the forum. Also an enthusiastic contributor to Wikipedia and Wikidata. He crusher of irons in gyms and when he can he exercises in cycling as well. Science fiction fan.